Baguette

Form: Long and narrow (about 65 cm / 25.6 in.)

Country of origin: France

What distinguishes it from other methods of bread making: Direct addition of baker’s yeast

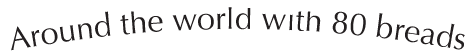

Category of bread: (3) Large number of sisters and cousins around the world: traditional French baguette; flûte, long but thicker than a baguette; ficelle, an extra-thin baguette; Viennese baguette; grissino (crisp breadstick); Turkish francala, etc.

Particularity: Crusty, easy to break off or cut in lengthwise direction to make an open-face or regular sandwich; many like the heel; a crusty baguette bought at your local baker’s rarely gets home without a bite or two missing

Ingredients: Wheat bread; baker’s yeast; salt; water

France

They say the baguette is a symbol of France and French culture. They may well be right. Nevertheless, it arrived late on the French scene. Here’s how.

For a long time – until the second half of the 14th century – bread was round, heavy (weighing as much as 10 pounds), and made with leavening. In both Paris and the provinces, everyone ate the same bread. Then Paris bread bakers sought innovation and started offering fantasy breads. They were distinguished by their shape, their weight (less than 6 pounds), and the whiteness of the crumb. The lightest breads were sprinkled with beer yeast, used by the Gauls in olden times, and then forgotten. These “buns” were the delight of Marie Antoinette, and were even named “Queen’s bread.”

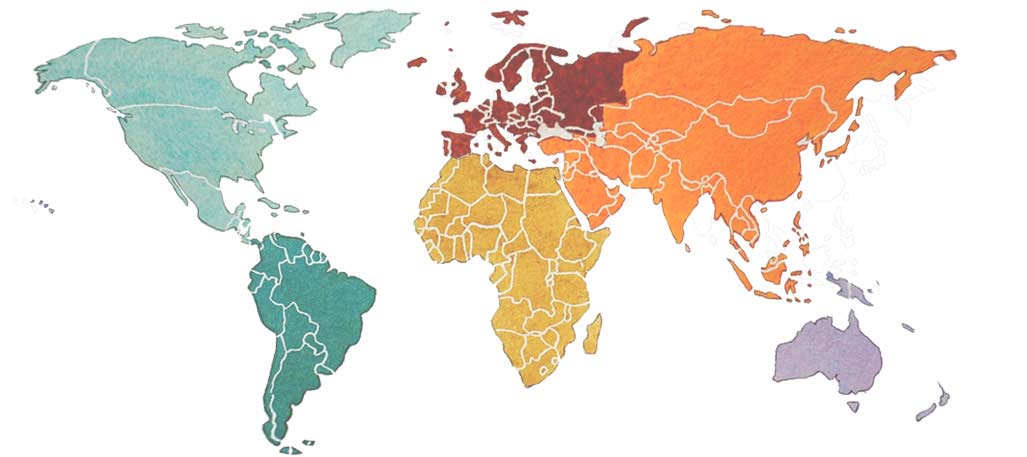

The fashion of making bread with yeast started again in 1838, when an Austrian artillery officer, Christophe Auguste Zang, opened a Viennese-style bakery at 92, rue de Richelieu in Paris. He offered a wide range of Viennese bread, highly sought after by Parisians, and soon imitated by his bread baker colleagues. It was the Baron Max de Springer who made Viennese bread fashionable in 1874 in Maisons-Alfort, with the creation of the first French factory for grain-based yeast.

At the end of the century, the baguette had almost come into being. What was missing? A bit of help from the government. To escape the tax on bread for “everyday consumption” (meaning with leavening), all bakers had to do was produce a bread that weighed less than 4 pounds and was longer than 70 cm / 27.5 in. Bread got lighter, weighing 250 grams, and longer, resembling Zang’s Viennese bread. In the 1920s, a baker whose name has been long forgotten had the idea of adding 5 to 7 knife slits to this slender, elegant bread. Perhaps the same baker gave it the name baguette; in any case, it remains a symbol of France.