Categories of bread

The endless varieties of bread that humans have been making from the beginning of time – first by women, later by men – is almost beyond belief. How is it possible, from a simple mixture of wheat or other grains, water, air and manual or mechanical force, to invent an almost infinite array of daily bread, each bearing a different name and meeting highly specific, demanding methods of production that have been passed down from generation to generation in villages, families and bakeries.

It’s rather like combining the 26 letters of the alphabet to write all the books and manuscripts in the world, except in the case of bread, we only have three or four letters to conjure up infinite mixtures to make up the immeasurable assortment of all the breads ever conceived. This minimum number of ingredients requires infinite talent.

So how do we find our bearings in this cornucopia of flours?

First, we have to consider the type of flour used, one that can be made into bread; the list is endless. These come for grains and cereals belonging to the grass, or Poaceae Gramineae, botanical family, carrying seeds. These seeds have the special property of containing insoluble proteins, called gliadin and glutenin. Once hydrated, they form a glutinous network that allows dough rolls to rise.

The grains most capable of being made into bread are wheat, in all its forms: 1) soft wheat or Triticum vulgare or aestivum; spelt; emmer, an ancient tetraploid wheat (Triticum dicoccum); Khorasan wheat, registered under the trademark KAMUT in the U.S., and durum wheat, and then 2) rye. However, this list of grains, appropriate for making breads, does not tell the entire story. We also have to take into account the various ways of making bread. Some mix grains containing little or no gluten (proteins), depending on agricultural demands and availability, such as oats, corn, millet, buckwheat, barley, rice, sorghum, and teff, as well as some seeds from other botanical families, such as quinoa, sesame, amaranth, etc. Even the roots of certain trees, such as manioc and tubers, yams, potatoes, etc., can be used. The breads we cover in this Around the World with 80 Breads come from these wide-ranging provisions; they are often included because of their inventive mixture of ingredients.

The criterion “appropriate for bread making” must therefore be extended beyond the flours listed above, which constitute highly structured dough, referred to as a “honeycomb structure.” The use of bread flour does not however mean that the result will be risen or leavened bread. Everything depends on the way the fermentation “ritual” is carried out. Dough to which leaven or yeast has been added may not be left long enough to rise before being thrown onto a griddle or onto the walls of a tannur or tandoor clay oven. That creates a whole range of names and descriptions, such as unleavened bread, griddlecakes, and leaf bread, which can often overlap.

Finally, to come back to the subject of cooking method, we have to remain flexible once again, and consider that it is not only bread straight from the oven, but also bread cooked on a griddle, under the ashes or hot sand, or even fried or poached in water, which still deserves to be considered as bread.

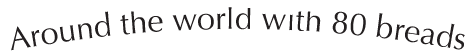

Once we have defined the “specifications” for what bread is and isn’t, we can break down all the different types of bread in the world into ten families or categories. This classification is based on the one used by Hubert Chiron in Jean-Philippe de Tonnac’s Dictionnaire universel du pain (published by Bouquins, Laffont 2010), or universal dictionary of bread.

Leaf bread

The dough is rolled out into ever-thinner layers. This is found in the form of rice sheets in Asia; brick pastry sheets in Tunisia and most of the Maghreb world; thin buckwheat pancakes, like those in Brittany in France; and thin matzo sheets or wafers, such as the sheets used to wrap nougat.

Topped or filled bread

Some topped breads, such as pizza, Lebanese or Jordanian manakich or Provencal pissaladières, have become stars of the fast food world. Some breads are better filled, such as Chinese boazi, Turkish pide, American rolls, etc.

Leavened crusty bread

Baguettes, and in a more general sense, French bread, are the first ones that come to mind when talking about “crusty” bread. Some Italian, Spanish, Greek, and Turkish breads also fit into this category.

Crisp bread

This tradition seems to be passed down from the northern cultures of Europe, perhaps from Sweden with its knäckebrod or “crisp bread”, as it is now called in supermarkets and shops. This category of bread is cooked twice, and is still made in numerous regions, including breads such as the Sardinian carasau or the Greek eptazymo.

Black bread

Black bread is generally made from rye flour, in regions where wheat has difficulty adapting to the climate, such Northern and Central Europe. Sourdough starter is used most often, and the dough is only slightly kneaded. Cooking time is extra long and most often in a bread pan.

Grain-free bread

Latin American cassava bread and Australian Aborigine bush bread, made since the dawn of time, contribute to a new category of bread, which may indeed seem exotic, but which is gaining immense popularity.

Breads not cooked in oven.

When fuel is hard to come by, when ovens are not part of the household landscape, it is therefore necessary to be highly inventive and think of other ways of cooking. Cooking bread on a griddle or metal plate laid directly onto a heat source is a universal practice. It is also possible to fry barley, sorghum or millet cakes, as they do in Africa and Central Asia. Small steam-cooked buns to which yeast or leaven is added are highly popular in China and Vietnam (mantou or baozi) or Ladakh and Tibet (dimo or trimo). They can be stuffed with meat, vegetables, a mixture of meat and vegetables, red bean paste, etc.

English-style white sandwich bread; Vienna-style soft-crumbed, crusty bread; dumplings

These breads, in a category distinctly on their own, mark particular differences in terms of cultural taste when it comes to food. While crusty bread brings the Mediterranean to mind, English-style white sandwich bread, which might be referred to as “crust-free”, is made with a dough to which fat and sugar are added, and is usually baked in an open or closed bread tin in order to ensure that it remains soft. This type of bread remains firmly entrenched in the English-speaking world, and can now be found in Europe and Russia. We might also add to this category bread made with grains that are not normally considered appropriate for bread making (rice, millet, etc.), made into soft bread-like dumplings.

Flat bread

Flat bread is mainly eaten in the Mediterranean, in Central Asia, and in Latin America. It is cooked on a griddle or in ovens called al-tannour in Arabic, derived from the word “athanor,” which comes from the world of alchemy. In this category, we can list Indian, Pakistani and Afghani naan; Tibetan balep korkun; American Indian cassava bread; Venezuelan arepa, etc. Seized at a very high temperature, this bread has the particularity of forming a pocket or “balloon” which collapses after cooking, thus giving it its special qualities. They are generally filled, unless they are torn off and used to pick up other food.

Ritual breads

Depending on the religious or traditional folklore calendar, bread makers open all the stops when it comes to making exceptional bread for these special occasions. Fat, sugar, and a myriad of ingredients are added to make brioche-like breads, such as kugelhopf, panettone, mouna, cougnou, etc.; breads that verge on being cakes, such as Irish barmbrack, made for Halloween; and other small breads, such as Peruvian t’anta wawas, for All Saints’ Day and the Day of the Dead.